ASSEMBLE

The following interview is part of the book New Commons for Europe, which is the transcript of conversations that occurred during the Bedford Tapes Symposium at the Architectural Association in London on 09.12.2016.

On 9 December 2016 the Architectural Association in London hosted The Bedford Tapes, an event that brought together architects and experts from all over Europe. New Commons for Europe captures the vitality and the doubts of a new generation of architects living at a key moment in the history of the European Union and questioning the role of the profession and the architect's ability to produce projects and spaces for the common good with an alternative set of resources and profit structure. After the conference a series of interviews were conducted with participants in London, Berlin, Brussels, Paris, Lisbon and Bucharest. The book chronicles both the event and the interviews, which have developed into an ongoing European conversation between architectural figures that takes a new reading of the boundaries of the discipline and its interactions with political, economic and social factors.

Anthony Engi Meacock I’m a part of Assemble. We are a collective of fifteen to nineteen people, depending on the criteria you use. We came together to build a single project which then started a collective working practice. I am going to talk about a collection of work, not a single project. The work is situated in Granby, which is located in a central area of Liverpool. Its growth was directly connected to the docks, and as a result it was one of the first true multicultural areas of the United Kingdom – through the docks, beginning in the nineteenth century, a huge influx of Somalis and other migrants came to the area. It had a really vibrant political scene; it was where much of the support for Nelson Mandela came from in the United Kingdom.

The area had a very active life, but one that was quite challenging to the status quo. Deindustrialisation of the city and the port had a heavy effect on the area. Things came to a head in 1981 following the closure of the ports and a huge rise in social problems. Ignited by an incident of police brutality, the area erupted in a series of outbursts that have been described as race riots. But when you speak to people there who lived through this period, they characterised the riots as based much more on class, as the area is very mixed ethnically and racially.

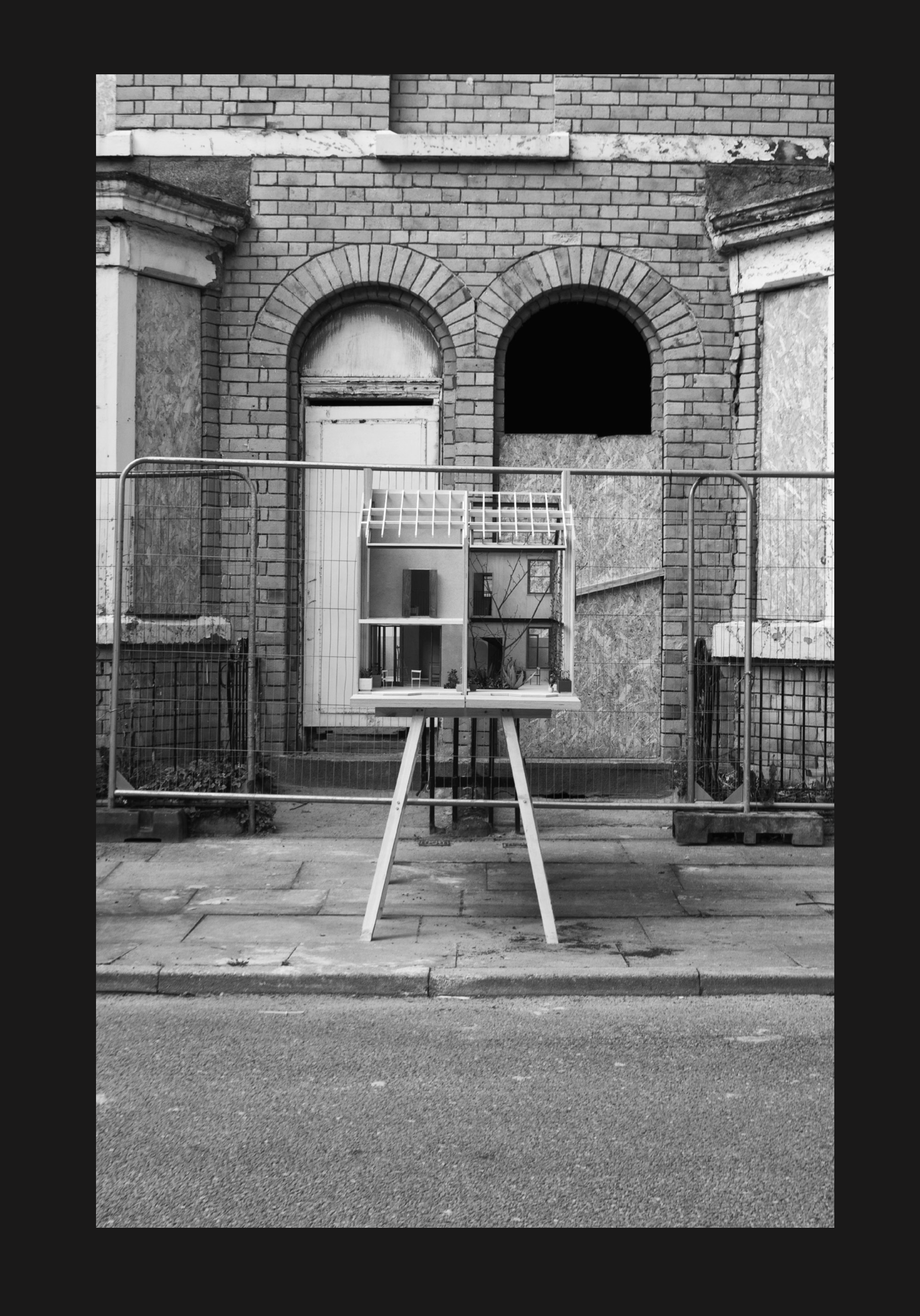

The response from local and national government, rather than tackle the social problems that had resulted in this mass disenfranchisement: poverty and crime, was to essentially clear the area and break it up. This is a map showing the areas identified for demolition. These four streets are the last surviving original houses and this is where our work is focused. This was in 2007 – the council forced out the residents and planned to demolish the area to then rebuild lower density housing that would have increased value, under a scheme called ‘manage decline’ – which is as negative as it sounds. Obviously, the key thing missing here is the idea of civic functions within the city. The council rebuilding programme was exclusively focused on the implementation of housing in a suburban model with no proposals for replacing shops, pubs, schools – or anything that could maintain the existing communal infrastructure.

Granby Street is the main street that dissects the whole block. It was a really vibrant high street that was intentionally destroyed except for a tiny cluster at the northern part. This cluster, which was empty, still retained a civic structure and appearance. The result of this clearance – quite predictably so for us – was that crime did not go away, gang activity increased in the vacuum.

In recent years, this council policy has been accepted as a mistake, which presents an opportunity. We entered the scene when this moment of failure happened. Because the waves of development from the 1980s and 1990s had really failed to deliver on their social promises, that had driven up prices and demand, left crime to itself, and avoided creating any kind of social infrastructure, the council was interested in trying something new.

Here a group of residents remained – mainly those who owned their homes, partly driven by the fact that if everyone is forced out of the area, suddenly your house is worth nothing and you can’t get out, partly as it was a place where people had grown up – about ten on the street. And in response to an extreme situation of deprivation they were taking matters into their own hands from the local council’s total abdication of social responsibility. Instead of being tired of looking at empty streets, the residents painted the window frames and houses so they didn’t look empty anymore. The council has a habit of demolishing buildings for no real reason, so this graffiti appeared as a kind of joke – and protest – as if the council would knock the buildings over by mistake.

The idea of this small axis of agency, a small axis where you can take control, increased the value of a place that is viewed as having no value. We also tried to change the perception of the site, making a project distinct from the council’s approach.

After a series of unsuccessful attempts to solve the crisis in the area and a series of broken promises by developers, the residents felt unheard and distraught. When we met them it really felt like an opportunity to help make something happen. People in the city have a huge amount of power if they take it. But often the system tries to ignore or suppress that power. We worked with the residents to develop a strategy of incremental improvement using the small pockets of funding available; what emerged was a masterplan and co-inhabitation of the street for an extended period of time.

This is a post-rationalisation drawing showing the activities at our adopted base – number 48: the front room was used by the builders when the building started happening, the basement was used as storage for the street market and to help the gardening, the back garden served as a kind of impromptu workshop for a collaborative project making items for the houses, and we stayed in the top floor. Here we regularly met with the residents to collectively develop and evaluate the development model for the area – documenting what was valuable, what was functional, what was really successful there, and also documenting the failures, the obvious problems.

This was a strategy where, instead of a tabula rasa and the hope that somehow a community emerges, you build from the amazing existing social infrastructure – a far more piecemeal, careful and incremental way of building. This is the idea of accretion that enables a much more gradual development means that you can adapt, change and evolve as you go.

The residents established a Community Land Trust (CLT) and secured a grant from the National Lottery Fund, which enabled us to access further grants from the Homes and Communities Agency, the council, and other charitable loans. This funded the restoration of the first ten houses. The aim was proving that, while these houses were not financially viable to restore in a normal development model and that the council was giving them away for a pound, we could do these up for very little money and far less than a new-build would cost.

This was a very careful, slow approach with a lot of compromise. We tried to keep the identity of the houses through low-cost interventions. This does not mean that the quality is not good, it simply means that we can do a lot with not so much.

For example, we kept the pitched roof structure that gives the house a charm that a spec building would never have, took care in the choices of materials and focused effort on those extra bits – that we refer to as embellishments – that can transform a very pragmatic, even boring shell into something that could be thought of as a home. And that could also take on the character of the people moving in – something they could identify with. Moreover, the series of products and items show that love has been taken in the process. We provided a complementary set of skills that are different from what you find among the residents and helped provide the extra bit of energy to bring ideas to fruition.

We have a strong belief that the functioning of a city relies on more than housing alone. You need civic functions, shops, etc. Here the production of ‘embellishments’ slowly evolved into the opportunity to create local economic activity, which led to the Granby Workshop.

The Turner Prize offered the opportunity for large exposure and secure funding for a new social enterprise. The products that were designed for the houses – sometimes with the residents, sometimes with people in Liverpool – are produced in Granby both taking advantage of existing skills and training new skills. They are for sale, initially during the Turner Prize and now available online. The income is reinvested in the neighbourhood – the ambition is to create a new business in the area that functions within the city. It is now in its really early stages and I don’t know if it will necessarily work but the indications are positive. The series of products are very much about revealing the hand that made them – a series of processes where the handmade is manifested. You are aware of the method they were made with – you have the printed fabric, the pressed ceramic, the lights, the wood-fired doorknob... they all leave a distinctive idea that these things are not necessarily expensive to make, but there is an understanding that these are made by individuals who have their own kind of agency.

This is a piecemeal development where housing comes first and it then generates interest and new money comes in. The workshop was then set up to exploit that and now, in the middle of the site, you can see the glass roof, where we are working on a project which explores what communal infrastructure can be. You could call it a community centre but one that isn’t cheap and miserable and based on a logic of economy that feels very false. In fact with the same economy you can build something extraordinary.

An image had existed for a while when we opened the door to one of the houses and there was a tree growing in it. Gardening and other collective activity has been incredibly beneficial, and so a space that supported those activities in the area seemed very important.

We also had an opportunity as two houses had been omitted from the original restoration work; rebuilding them wasn’t economically viable because they were in an advanced state of decay. Here again, it is thanks to the publicity and the media and political focus on Granby that we have been able to get further funds and to establish a different economic model to refurbish these two houses into an extraordinary communal space – and one that is not only dependent on public subsidies.

We secured Arts Council funding to deliver a new type of space: one that provides a connection to the past by showing the past reality of the houses. At the same time, the project will, through hosting a series of residencies, support the symbiotic working relationships (like the residents and ours) that have been deeply beneficial in delivering the work in Granby. So this space is also a look to the future. One house remains totally open as the garden space. It is a space where you might have a children’s birthday party one day, a market happening the next day. The other house functions like a meeting room, and on the first floor above it is an Airbnb type of space that enables both a collective guest house for the whole street or for practitioners, artists, etc, to be invited to the area. It allows for the continuation of this symbiotic relationship where people with different practices can work in the area. By trying to gather people and energy, you can create a more resilient structure.

This is the garden space and the common room, which reveals the studio behind the bedroom. These spaces provide enough income from exploiting opportunities for artist-led investment, which is not cost-neutral but starts paying for other improvements in the area. That’s the hope – to incrementally improve this area through an approach we feel is valuable and is applicable to other spaces and other places.

Kathryn Firth Does your job ever finish? You have taken a mentoring role that ties into the issue of attitude and role of the architect. The word ‘architect’ seems to be insufficient in describing what you are doing here. One could see your role carrying on forever. What is the end point? Gentrification?

AEM I don’t know when we finish. The idea is that we actively employ people in the workshops and steadily withdraw, so they end up being in the director’s seat. Gentrification might be a real issue. In this case you have to raise property prices, because they had no value, but slowly to avoid displacing people. This was something that the CLT was really aware of as well. They inserted a clause in the sales contracts for the properties that owners can sell it only at a rate that is tied to the median income of the area. In terms of the effect more widely, it is probably acting as a gentrifier for properties around it. But it is difficult to know exactly what you can do about that. As long as you are conscious you can mitigate as best as you can. It might be a disaster, it might be gentrified and be really horrible. But it feels too early to assess.

Pooja Agrawal When you were first approached, you probably didn’t know what you were going to do. I guess the whole idea was that you were writing the brief with the clients. The architect/client roles were slightly more blurred than usual and over time you developed the scope of the project. My question is: how do you make this sustainable? I am guessing you do not fill out timesheets.

AEM Actually we do. We are a business, we get paid, we charge fees. We try and divide the work and we are very conscious of what can be exploited for more money without being a problem, and we do that. The CLT is really good – they pay us, they think the work has value, so it wasn’t ever really a challenge. The residents were quite forthright: ‘You have to get paid! We do not want to exploit you, come on, invoice us!’ For the Winter Garden we worked very closely with other people to secure the funding from the Arts Council, so we took a bit of a risk, but compared to a competition it was a way lower risk than entering a competition with a brief that is written beforehand. The problem with competitions is that the briefs are often shit. Here we get to write our own brief, so we had so much control that it actually makes it far lower risk than some traditional architecture practice.

Audience The project seems to have a certain element of condescension because you are all upper middle class and you’re coming from a certain educational background and then you go into a deprived area. And the aestheticisation of the documentation of the process raises the question of how far this has become part of the construction of an architectural career. With the Turner Prize your practice has gone up in the market, you’ve gained value in the market of architects. What was your approach in the participatory process with the community, what was the exchange? Because the doorknobs, etc, have something a bit exclusive to them. Did their situation really change? Are they politically activated?

Jeremy Till As a person who has been there several times I would say: don’t get too distracted by the doorknobs because they are a fraction of the process and the really interesting stuff is the legal and tenure side of building community interest and convincing the council to give this entire street to the residents. That’s where the project is for me – not the tiles and the doorknobs.

AEM It’s probably better to ask the residents about their situation rather than me, because I am obviously always going to say that it’s great. Yes we are a bunch of very privileged people and I guess the question is can you use that privilege in different ways for good or bad – you can try to do something you believe in. Often people get criticised for being privileged and having the audacity to think that they can do something positive, which I think is unfair. Here we have tried to use the privilege we have to positive effect – and how successful that is, is how it should be judged

Jeremy Till When you were presenting the staircase it struck me how classically architectural that was: why don’t you present the project as a set of spreadsheets? Because that, for me, seems to be what your amazing skills are – to actually manipulate spreadsheets rather than to manipulate the doorknobs.

AEM That’s ... yeah, it is a really good point!

New Commons for Europe is sold-out on Spector Books website but last copies are available online